Okay. I admit it. That’s a linkbait-y title. In my defense, though, the only audience that would be successfully baited by it, I think, are digital analysts, statisticians, and data scientists. And, that’s who I’m targeting, albeit for different reasons:

- Digital analysts — if you’re reading this then, hopefully, it may help you get over an initial hump on the topic that I’ve been struggling mightily to clear myself.

- Statisticians and data scientists — if you’re reading this, then, hopefully, it will help you understand why you often run into blank stares when trying to explain a t-test to a digital analyst.

If you are comfortably bridging both worlds, then you are a rare bird, and I beg you to weigh in in the comments as to whether what I describe rings true.

The Premise

I took a college-level class in statistics in 2001 and another one in 2010. Neither class was particularly difficult. They both covered similar ground. And, yet, I wasn’t able to apply a lick of content from either one to my work as a web/digital analyst.

Since early last year, as I’ve been learning R, I’ve also been trying to “become more data science-y,” and that’s involved taking another run at the world of statistics. That. Has. Been. HARD!

From many, many discussions with others in the field — on both the digital analytics side of things and the more data science and statistics side of things — I think I’ve started to identify why and where it’s easy to get tripped up. This post is an enumeration of those items!

As an aside, my eldest child, when applying for college, was told that the fact that he “didn’t take any math” his junior year in high school might raise a small red flag in the admissions department of the engineering school he’d applied to. He’d taken statistics that year (because the differential equations class he’d intended to take had fallen through). THAT was the first time I learned that, in most circles, statistics is not considered “math.” See how little I knew?!

Terminology: Dimensions and Metrics? Meet Variables!

Historically, web analysts have lived in a world of dimensions. We combine multiple dimensions (channel + device type, for instance) and then put one or more metrics against those dimensions (visits, page views, orders, revenue, etc.)

Statistical methods, on the other hand, work with “variables.” What is a variable? I’m not being facetious. It turns out it can be a bit a mind-bender if you come at it from a web analytics perspective:

- Is device type a variable?

- Or, is the number of visits by device type a variable?

- OR, is the number of visits from mobile devices a variable?

The answer… is “Yes.” Depending on what question you are asking and what statistical method is being applied, defining what your variable(s) are, well, varies. Statisticians think of variables as having different types of scales: nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio. And, in a related way, they think of data as being either “metric data” or “nonmetric data.” There’s a good write-up on the different types — with a digital analytics slant — in this post on dartistics.com.

It may seem like semantic navel-gazing, but it really isn’t: different statistical methods work with specific types of variables, so data has to be transformed appropriately before statistical operations are performed. Some day, I’ll write that magical post that provides a perfect link between these two fundamentally different lenses through which we think about our data… but today is not that day.

Atomic Data vs. Aggregated Counts

In R, when using ggplot to create a bar chart that uses underlying data that looks similar to how data would look in Excel, I have to include a parameter that is stat="identity". As it turns out, that is a symptom of the next mental jump required to move from the world of digital analytics to the world of statistics.

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel:

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel:

- In web analytics, we think: “this is how many (a count) visitors to the site came from each of referring sites, paid search, organic search, etc.”

- In statistics, typically, the framing would be: “here is a list (row) for each visitor to the site, and each visitor is identified as being visiting from referring sites, paid search, organic search, etc.” (or, possibly, “each visitor is flagged as being yes/no for each of: referring sites, paid search, organic search, etc.”… but that’s back to the discussion of “variables” covered above).

So, in my bar chart example above, R defaults to thinking that it’s making a bar chart out of a sea of data, where it’s aggregating a bunch of atomic observations into a summarized set of bars. The stat="identity" argument has to be included to tell R, “No, no. Not this time. I’ve already counted up the totals for you. I’m telling you the height of each bar with the data I’m sending you!”

When researching statistical methods, this comes up time and time again: statistical techniques often expect a data set to be a collection of atomic observations. Web analysts typically work with aggregated counts. Two things to call out on this front:

- There are statistical methods (a cross tabulation with a Chi square test for independence is one good example) that work with aggregated counts. I realize that. But, there are many more that actually expect greater fidelity in the data.

- Both Adobe Analytics (via data feeds, and, to a clunkier extent, Data Warehouse) and Google Analytics (via the GA360 integration with Google BigQuery) offer much more atomic level data than the data they provided historically through their primary interfaces; this is one reason data scientists are starting to dig into digital analytics data more!

The big, “Aha!” for me in this area is that we often want to introduce pseudo-granularity into our data. For instance, if we look at orders by channel for the last quarter, we may have 8-10 rows of data. But, if we pull orders by day for the last quarter, we have a much larger set of data. And, by introducing granularity, we can start looking at the variability of orders within each channel. That is useful! When performing a 1-way ANOVA, for instance, we need to compare the variability within channels to the variability across channels to draw conclusions about where the “real” differences are.

This actually starts to get a bit messy. We can’t just add dimensions to our data willy-nilly to artificially introduce granularity. That can be dangerous! But, in the absence of truly atomic data, some degree of added dimensionality is required to apply some types of statistical methods. <sigh>

Samples vs. Populations

The first definition for “statistics” I get from Google (emphasis added) is:

“the practice or science of collecting and analyzing numerical data in large quantities, especially for the purpose of inferring proportions in a whole from those in a representative sample.”

Web analysts often work with “the whole.” Unless we consider historical data the sample and the “whole” including future web traffic. But, if we view the world that way — by using time to determine our “sample” — then we’re not exactly getting a random (independent) sample!

We’ve also been conditioned to believe that sampling is bad! For years, Adobe/Omniture was able to beat up on Google Analytics because of GA’s “sampled data” conditions. And, Google has made any number of changes and product offerings (GA Premium -> GA 360) to allow their customers to avoid sampling. So, Google, too, has conditioned us to treat the word “sampled” as having a negative connotation.

To be clear: GA’s sampling is an issue. But, it turns out that working with “the entire population” with statistics can be an issue, too. If you’ve ever heard of the dangers of “overfitting the model,” or if you’ve heard, “if you have enough traffic, you’ll always find statistical significance,” then you’re at least vaguely aware of this!

So, on the one hand, we tend to drool over how much data we have (thank you, digital!). But, as web analysts, we’re conditioned to think “always use all the data!” Statisticians, when presented with a sufficiently large data set, like to pull a sample of that data, build a model, and then test the model with another sample of the data. As far as I know, neither Adobe nor Google have an, “Export a sample of the data” option available natively. And, frankly, I have yet to come across a data scientist working with digital analytics data who is doing this, either. But, several people have acknowledged this is something that should be done in some cases.

I think this is going to have to get addressed at some point. Maybe it already has been, and I just haven’t crossed paths with the folks who have done it!

Decision Under Uncertainty

I’ve saved the messiest (I think) for last. Everything on my list to this point has been, to some extent, mechanical. We should be able to just “figure it out” — make a few cheat sheets, draw a few diagrams, reach a conclusion, and be done with it.

But, this one… is different. This is an issue of fundamental understanding — a fundamental perspective on both data and the role of the analyst.

Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in The Cartoon Guide to Statistics, which devotes an early chapter to the subject. It actually goes all the way back to the 1600s and an exchange between Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat and proceeds to walk through a dice-throwing example of probability theory. Alas! This is where the book lost me (although I still have it and may give it another go).

Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in The Cartoon Guide to Statistics, which devotes an early chapter to the subject. It actually goes all the way back to the 1600s and an exchange between Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat and proceeds to walk through a dice-throwing example of probability theory. Alas! This is where the book lost me (although I still have it and may give it another go).

Possibly related — although quite different — is something that Matt Gershoff of Conductrics and I have chatted about on multiple occasions across multiple continents. Matt posits that, really, one of the biggest challenges he sees traditional digital analysts facing when they try to dive into a more statistically-oriented mindset is understanding the scope (and limits!) of their role. As he put it to me once in a series of direct messages really boils down to:

- It’s about decision-making under uncertainty

- It’s about assessing how much uncertainty is reduced with additional data

- It must consider, “What is the value in that reduction of uncertainty?”

- And it must consider, “Is that value greater than the cost of the data/time/opportunity costs?”

The list looks pretty simple, but I think there is a deeper mindset/mentality-shift that it points to. And, it gets to a related challenge: even if the digital analyst views her role through this lens, do her stakeholders think this way? Methinks…almost certainly not! So, it opens up a whole new world of communication/education/relationship-management between the analyst and stakeholders!

For this area, I’ll just leave it at, “There are some deeper fundamentals that are either critical to understand or something that can be kicked down the road a bit.” I don’t know which it is!

What Do You Think?

It’s taken me over a year to slowly recognize that this list exists. Hopefully, whether you’re a digital analyst dipping your toe more deeply into statistics or a data scientist who is wondering why you garner blank stares from your digital analytics colleagues, there is a point or two in this post that made you think, “Ohhhhh! Yeah. THAT’s where the confusion is.”

If you’ve been trying to bridge this divide in some way yourself, I’d love to hear what of this post resonates, what doesn’t, and, perhaps, what’s missing!

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel:

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel: Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in

Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in

The show’s opening credits roll. Jamie and Adam stand in their workshop and survey the tools they have: welding equipment, explosives, old cars, Buster, ruggedized laptops, high-speed cameras, heavy ropes and chain, sheet metal, plexiglass, remote control triggers, and so on. They chat about which ones seem would be the most fun to do stuff with, and then they head their separate ways to build something cool and interesting.

The show’s opening credits roll. Jamie and Adam stand in their workshop and survey the tools they have: welding equipment, explosives, old cars, Buster, ruggedized laptops, high-speed cameras, heavy ropes and chain, sheet metal, plexiglass, remote control triggers, and so on. They chat about which ones seem would be the most fun to do stuff with, and then they head their separate ways to build something cool and interesting.

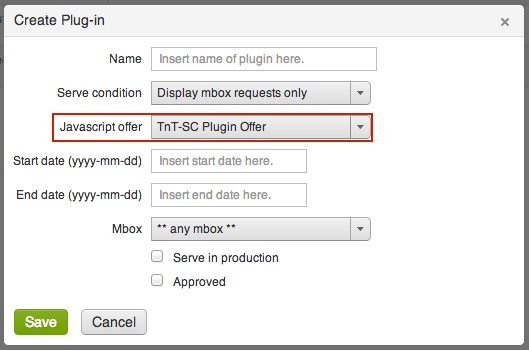

Then we simply configure the plug-in here:

Then we simply configure the plug-in here: The area surrounded by a red box is where you select the previously created HTML offer with your plug-in code. You also have the option to specify when the code gets fired. Typically you want it to only fire when a visitor becomes a member of a test or when test content (T&T offers) are being displayed and to do so, simply select, Display mbox requests only. If you wanted to, you can have your code fire on all mbox requests as that can be need sometimes. Additionally, you can limit the code firings to a particular mbox or even by certain date periods.

The area surrounded by a red box is where you select the previously created HTML offer with your plug-in code. You also have the option to specify when the code gets fired. Typically you want it to only fire when a visitor becomes a member of a test or when test content (T&T offers) are being displayed and to do so, simply select, Display mbox requests only. If you wanted to, you can have your code fire on all mbox requests as that can be need sometimes. Additionally, you can limit the code firings to a particular mbox or even by certain date periods. Now that we understand that, lets see what the integration gets you:

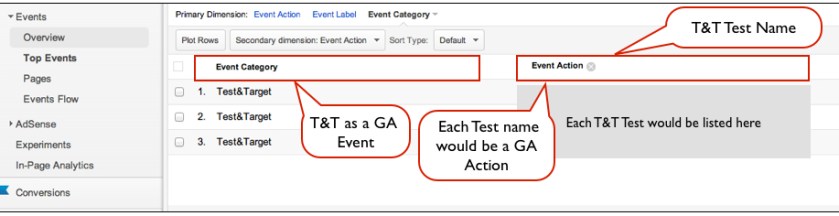

Now that we understand that, lets see what the integration gets you: What we have here is a report of a specific Google Analytics Event Category, in this case the Test&Target Event. Most of my clients have many Event Categories so it’s important to classify Test&Target as a separate Event and this plug-in code does that for you.

What we have here is a report of a specific Google Analytics Event Category, in this case the Test&Target Event. Most of my clients have many Event Categories so it’s important to classify Test&Target as a separate Event and this plug-in code does that for you. Here we can look at how a unique test and its experiences impacted given success events captured in Google Analytics. Typically, most organizations include their key success events for analysis in T&T but this integration is helpful if you want to look at success events not included in your T&T account or if you want to see how your test experiences impacted engagement metrics like time on site, page views, etc….

Here we can look at how a unique test and its experiences impacted given success events captured in Google Analytics. Typically, most organizations include their key success events for analysis in T&T but this integration is helpful if you want to look at success events not included in your T&T account or if you want to see how your test experiences impacted engagement metrics like time on site, page views, etc…. Earlier this year, I wrote about

Earlier this year, I wrote about

This diagram was titled “Analytics Maturity.” It’s true — slapping Google Analytics on your web site (behavioral data) is cheap and easy. It takes more effort to actually capture voice-of-the-customer (attitudinal) data; even if it’s with a “free” tool like

This diagram was titled “Analytics Maturity.” It’s true — slapping Google Analytics on your web site (behavioral data) is cheap and easy. It takes more effort to actually capture voice-of-the-customer (attitudinal) data; even if it’s with a “free” tool like

Photo courtesy of dno1967

Photo courtesy of dno1967

I was working with a client last week who was looking to update their lead scoring. This wasn’t any fancy-schmancy

I was working with a client last week who was looking to update their lead scoring. This wasn’t any fancy-schmancy  Avinash Kaushik has a great post today titled

Avinash Kaushik has a great post today titled