In a normal year, we’d be long past the point in the calendar where I had written a blog post on all of the exciting things I had seen at Adobe Summit. Unfortunately, nothing about this spring has been normal other than that Summit was in person again this year (yay!), because I was unable to attend. Instead, it was my wife and 3 of my kids that headed to Las Vegas the last week in March; they saw Taylor Swift in concert instead of Run DMC, and I stayed home with the one who had other plans.

And boy, does it sound like I missed a lot. I knew something was up when Adobe announced a new product analytics-based solution to jump into what has already been a pretty competitive battle. Then, another one of our partners, Brian Hawkins, started posting excitedly on Slack that historically Google-dominant vendors were gushing about the power of Analytics Workspace and Customer Journey Analytics (CJA). Needless to say, it felt a bit like three years of pent-up remote conference angst went from a simmer to a boil this year, and I missed all the action. But, in reading up on everyone else’s takes from the event, it sure seems to track with a lot of what we’ve been seeing with our own clients over the past several months as well.

Will digital analytics or product analytics win out?

Product analytics tools have been slowly growing in popularity for years; we’ve seen lots of our clients implement tools like Heap, Mixpanel, or Amplitude on their websites and mobile apps. But it has always been in addition to, not as a replacement for traditional digital analytics tools. 2022 was the year when it looked like that might change, for two main reasons:

- Amplitude started adding traditional features like marketing channel analysis into its tool that had previously been sorely lacking from the product analytics space;

- Google gave a swift nudge to its massive user base, saying that, like it or not, it will be sunsetting Universal Analytics, and GA4 will be the next generation of Google Analytics.

These two events have gotten a lot of our clients thinking about what the future of analytics looks like for them. For companies using Google Analytics, does moving to GA4 mean that they have to adopt a more product analytics/event driven approach? Is GA4 the right tool for that switch?

And for Adobe customers, what does all this mean for them? Adobe is currently offering Customer Journey Analytics as a separate product entirely, and many customers are already pretty satisfied with what they have. Do they need to pay for a second tool? Or can they ditch Analytics and switch to CJA without a ton of pain? The most interesting thing to me about CJA is that it offers a bunch of enhancements over Adobe Analytics – no limits on variables, uniques, retroactivity, cross-channel stitching – and yet many companies have not yet decided that the effort necessary to switch is worth it.

Will companies opt for a simple or more customizable model for their analytics platform?

Both GA4 and Amplitude are on the simpler side of tools to implement; you track some events on your website, and you associate some data to those events. But the data model is quite similar between the two (I’m sure this is an overstatement they would both object to, but in terms of the data they accept, it’s true enough). On the other hand, for CJA, you really need to define the data model up front – even if you leverage one of the standard data models Adobe offers. And any data model is quite different from the model used by Omniture SiteCatalyst / Adobe Analytics for the better part of the last 20 years – though it probably makes far more intuitive sense to a developer, engineer, or data scientist.

Will some companies answer to the “GA or Adobe” question be “both?”

One of the more surprising things I heard coming out of Summit was the number of companies considering using both GA4 and CJA to meet their reporting needs. Google has a large number of loyal customers – Universal Analytics is deployed on the vast majority of websites worldwide, and most analysts are familiar with the UI. But GA4 is quite different, and the UI is admittedly still playing catchup to the data collection process itself.

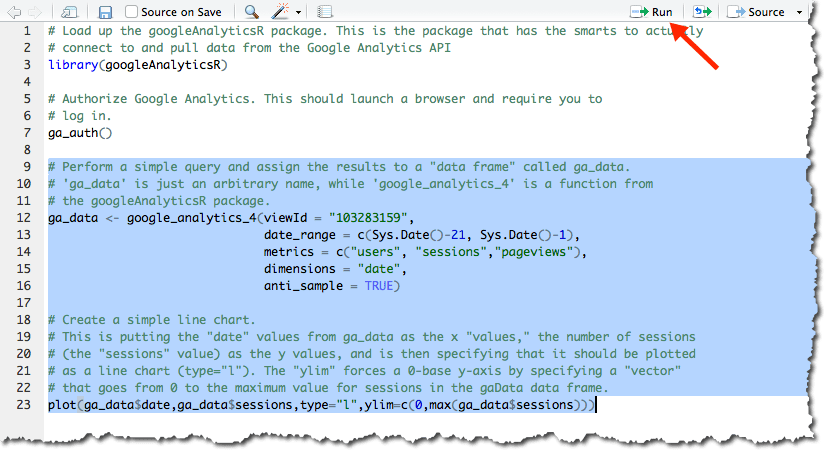

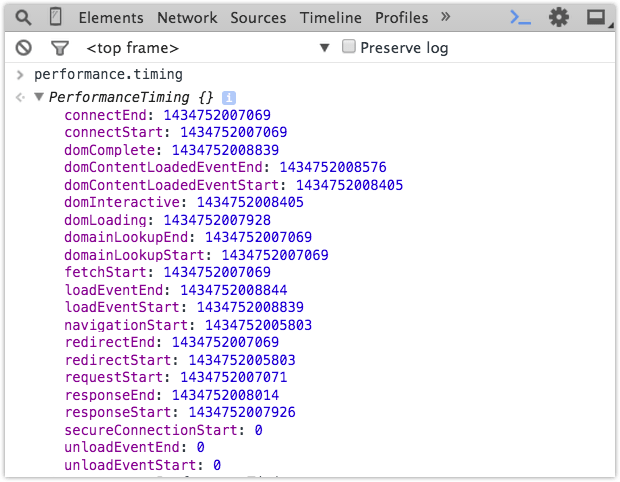

At this point, a lot of heavy GA4 analysis needs to be done either in Looker Studio or BigQuery, which requires SQL (and some data engineering skills) that many analysts are not yet comfortable with. But as I mentioned above, the GA4 data model is relatively simple, and the process of extracting data from BigQuery and moving it somewhere else is straightforward enough that many companies are looking for ways to keep using GA4 to collect the data, but then use it somewhere else.

To me, this is the most fascinating takeaway from this year’s Adobe Summit – sometimes it can seem as if Adobe and Google pretend that the other doesn’t exist. But all of a sudden, Adobe is actually playing up how CJA can help to close some of the gaps companies are experiencing with GA4.

Let’s say you’re a company that has used Universal Analytics for many years. Your primary source of paid traffic is Google Ads, and you love the integration between the two products. You recently deployed GA4 and started collecting data in anticipation of UA getting cut off later this year. Your analysts are comfortable with the old reporting interface, but they’ve discovered that the new interface for GA4 doesn’t yet allow for the same data manipulations that they’ve been accustomed to. You like the Looker Studio dashboards they’ve built, and you’re also open to getting them some SQL/BigQuery training – but you feel like something should exist between those two extremes. And you’re pretty sure GA4’s interface will eventually catch up to the rest of the product – but you’re not sure you can afford to wait for that to happen.

At this point, you notice that CJA is standing in the corner, waving both hands and trying to capture your attention. Unlike Adobe Analytics, CJA is an open platform – meaning, if you can define a schema for your data, you can send it to CJA and use Analysis Workspace to analyze it. This is great news, because Analysis Workspace is probably the strongest reporting tool out there. So you can keep your Google data if you like it – keep it in Google, leverage all those integrations between Google products – but also send that same data to Adobe and really dig in and find the insights you want.

I had anticipated putting together some screenshots showing how easy this all is – but Adobe already did that for me. Rather than copy their work, I’ll just tell you where to find it:

- If you want to find out how to pull historical GA4 data into CJA, this is the article for you. It will give you a great overview on the process.

- If you want to know how to send all the data you’re already sending to GA4 to CJA as well, this is the article you want. There’s already a Launch extension that will do just that.

Now maybe you’re starting to put all of this together, but you’re still stuck asking one or all of these questions:

“This sounds great but I don’t know if we have the right expertise on our team to pull it off.”

“This is awesome. But I don’t have CJA, and I use GTM, not Launch.”

“What’s a schema?”

Well, that’s where we come in. We can walk you through the process and get you where you want to be. And we can help you do it whether you use Launch or GTM or Tealium or some other tag management system. The tools tend to be less important to your success than the people and the plans behind them. So if you’re trying to figure out what all this industry change means for your company, or whether the tools you have are the right ones moving forward, we’re easy to find and we’d love to help you out.

Photo credits: Thumbnail photo is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to