Update – February 2017: Since this post was originally written in January 2016, there have been a lot of developments in the world of R when it comes to Google Analytics. Most notably, the googleAnalyticsR package was released. That package makes a number of aspects of using R with Google Analytics quite a bit easier, and it takes advantage of the v4 API for Google Analytics. As such, this post has been updated to use this new package. In addition, in the fall of 2016, dartistics.com was created — a site dedicated to using R for digital analytics. The Google Analytics API page on that site is, in some ways, redundant with this post. I’ve updated this post to use the googleAnalyticsR package and, overall, to be a bit more streamlined.

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to Step 1.)

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to Step 1.)

R is like a bicycle. Or, rather, learning R is like learning to ride a bicycle.

Someone once pointed out to me how hard it is to explain to someone how to ride a bicycle once you’ve learned to ride yourself. That observation has stuck with me for years, as it applies to many learned skills in life. It can be incredibly frustrating (but then rewarding) to get from “not riding” to “riding.” But, then, once you’re riding, it’s incredibly hard to articulate exactly what clicked that made it happen so that you can teach someone else how to ride.

(I really don’t want you to get distracted from the core topic of this post, but if you haven’t watched the Backwards Bicycle video on YouTube… hold that out as an 8-minute diversion to avail yourself of should you find yourself frustrated and needing a break midway through the steps in this post.)

I’m starting to think, for digital analysts who didn’t come from a development background, learning R can be a lot like riding a bike: plenty of non-dev-background analysts have done it…but they’ve largely transitioned to dev-speak once they’ve made that leap, and that makes it challenging for them to help other analysts hop on the R bicycle.

This post is an attempt to get from “your parents just came home with your first bike” to “you pedaled, unassisted, for 50 feet in a straight line” as quickly as possible when it comes to R. My hope is that, within an hour or two, with this post as your guide, you can see your Google Analytics data inside of RStudio. If you do, you’ll actually be through a bunch of the one-time stuff, and you can start tinkering with the tool to actually put it to applied use. This post is written as five steps, and Step 1 and Step 2 are totally one-time things. Step 3 is possibly one-time, too, depending on how many sites you work on.

Why Mess with R, Anyway?

Before we hop on the R bike, it’s worth just a few thoughts on why that’s a bike worth learning to ride in the first place. Why not just stick with Excel, or simply hop over to Tableau and call it a day? I’m a horrible prognosticator, but, to me, it seems like R opens up some possibilities that the digital analysts of the future will absolutely need:

- It’s a tool designed to handle very granular/atomic data, and to handle it fairly efficiently.

- It’s shareable/replicable — rather than needing to document how you exported the data, then how you adjusted it and cleaned it, you actually have the steps fully “scripted;” they can be reliably repeated week in and week out, and shared from analyst to analyst.

- As an open source platform geared towards analytics, it has endless add-ons (“packages”) for performing complex and powerful operations.

- As a data visualization platform, it’s more flexible than Excel (and, it can do things like build a simple histogram with 7 bars from a million individual data points…without the intermediate aggregation that Excel would require).

- It’s a platform that inherently supports pulling together diverse data sets fairly easily (via APIs or import).

- It’s “scriptable” — so it can be “programmed” to quickly combine, clean, and visualize data from multiple sources in a highly repeatable manner.

- It’s interactive — so it can also be used to manipulate and explore data on the fly.

That list, I realize, is awfully “feature”-oriented. But, as I look at how the role of analytics in organizations is evolving, these seem like features that we increasingly need at our disposal. The data we’re dealing with is getting larger and more complex, which means it both opens up new opportunities for what we can do with it, and it requires more care in how the fruits of that labor get visualized and presented.

If you need more convincing, check out Episode #019 of the Digital Analytics Power Hour podcast with Eric Goldsmith — that discussion was the single biggest motivator for why I spent a good chunk of the holiday lull digging back into R.

A Quick Note About My Current R Expertise

At this point, I’m still pretty wobbly on my R “bike.” I can pedal on my own. I can even make it around the neighborhood…as long as there aren’t sharp curves or steep inclines…or any need to move particularly quickly. As such, I’ve had a couple of people weigh in (heavily — there are some explanations in this post that they wrote out entirely… and I learned a few things as a result!):

Jason and Tom are both cruising pretty comfortably around town on their R bikes and will even try an occasional wheelie. Their vetting and input shored up the content in this post considerably.

So, remember:

- This is an attempt to be the bare minimum for someone to get their own Google Analytics data coming into RStudio via the Google Analytics API.

- It’s got bare minimum explanations of what’s going on at each step (partly to keep from tangents; partly because I’m not equipped to go into a ton of detail).

If you’re trying to go from “got the bike” (and R and RStudio are free, so they’re giving bikes away) to that first unassisted trip down the street, and you use this post to do so, please leave a comment as to if/where you got tripped up. I’ll be monitoring the comments and revising the post as warranted to make it better for the next analyst.

I’m by no means the first person to attempt this (see this post by Kushan Shah and this post by Richard Fergie and this post by Google… and now this page on dartistics.com and this page on the googleAnalyticsR site). I’m penning this post as my own entry in that particular canon.

Step 1: Download and Install R and RStudio

This is a two-step process, but it’s the most one-time of any part of this:

- Install R — this is, well, R. Ya’ gotta have it.

- Install RStudio (desktop version) — this is one of the most commonly used IDEs (“integrated development environments”); basically, this is the program in which we’ll do our R development work — editing and running our code, as well as viewing the output. (If you’ve ever dabbled with HTML, you know that, while you can simply edit it in a plain text editor, it’s much easier to work with it in an environment that color-codes and indents your code while providing tips and assists along the way.)

Now, if you’ve made it this far and are literally starting from scratch, you will have noticed something: there are a lot of text descriptions in this world! How long has it been since you’ve needed to download and install something? And…wow!… there are a lot of options for exactly which is the right one to install! That’s a glimpse into the world we’re diving into here. You won’t need to be making platform choices right and left — the R script that I write using my Mac is going to run just fine on your Windows machine* — but the world of R (the world of development) sure has a lot of text, and a lot of that text sometimes looks like it’s in a pseudo-language. Hang in there!

* This isn’t entirely true…but it’s true enough for now.

Step 2: Get a Google API Client ID and Client Secret

[February 2017 Update: I’ve actually deleted this entire section after much angst and hand-wringing. One of the nice things about googleAnalyticsR — the “package” we’ll be using here shortly — is that the authorization process is much easier. The big caveat is that, for that to work without creating your own Google Developer Project API client ID and client secret is that you will be using the defaults for those. That’s okay — you’re not putting any of your data at risk, as you will have to log in to your Google account a web browser when your script runs. But, there’s a chance that, at some point, the default app will hit the limit of daily Google API calls, at which point you’ll need your own app and credentials. See the Using Your Own Google Developer Project API Key and Secret section on the googleAnalyticsR Setup page for a bit more detail.]

Step 3: Get the View ID for the Google Analytics View

If the previous step is our way to enable R to actually prompt you to authenticate, this step is actually about pointing R to the specific Google Analytics view we’re going to use.

There are many ways to do this, but a key here is that the view ID is not the Google Analytics Property ID.

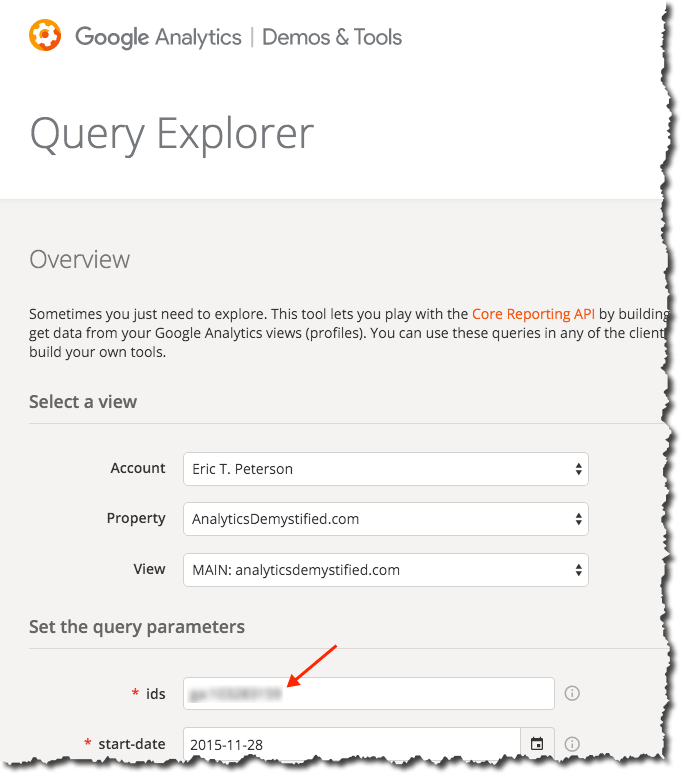

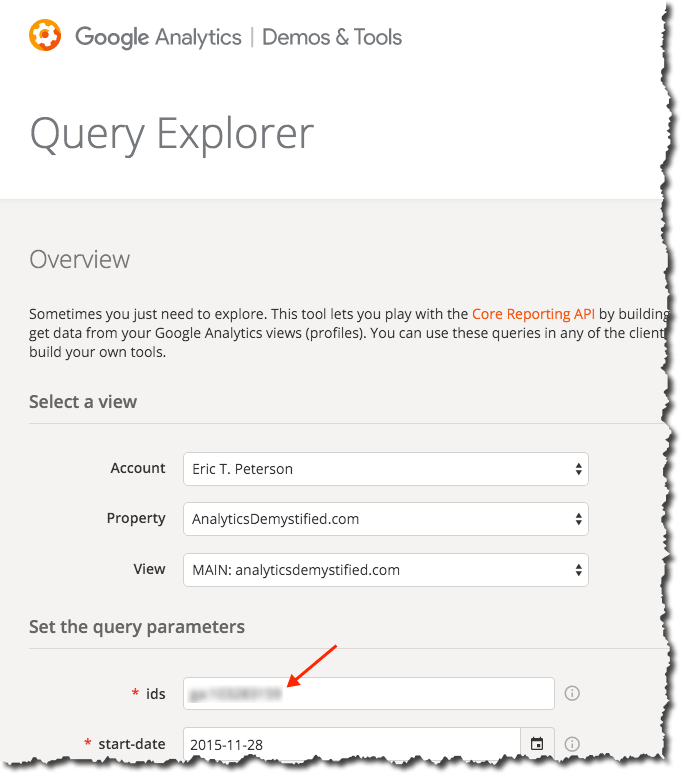

I like to just use the Google Analytics Query Explorer. If, for some reason, you’re not already logged into Google, you’ll have to authenticate first. Once you have been authenticated, you will see the screen shown below. You just need to drill down from Account to Property to View with the top three dropdowns to get to the view you want to use for this bike ride. The ID you want will be listed as the first query parameter:

You’ll need to record this ID somewhere (or, again, just leave the browser tab open while you’re building your script in a couple of steps).

Step 4: Launch RStudio and Get Clear on a Couple of Basic-Basic Concepts

Go ahead and launch RStudio (the specifics of launching it will vary by platform, obviously). You should get a screen that looks pretty close to the following (click to enlarge):

It’s worth hitting on each of these four panes briefly as a way to get a super-basic understanding of some things that are unique when it comes to working with R. For each of the four areas described below, you can insert, “…and much, much more” at the end.

Sticking to the basics:

- Pane 1: Source (this pane might not actually appear — Pane 2 may be full height; don’t worry about that; we’ll have Pane 1 soon enough!) — this is an area where you can both view data and, more importantly (for now), view and edit files. There’s lots that happens (or can happen) here, but the way we’re going to use it in this post is to work on an R script that we can edit, run, and save. We’ll also use it to view a table of our data.

- Pane 2: Console — this is, essentially, the “what’s happening now” view. But, it is also where we can actually enter R commands one by one. We’ll get to that at the very end of this post.

- Pane 3: Environment/Workspace/History — this keeps a running log of the variables and values that are currently “in memory.” That can wind up being a lot of stuff. It’s handy for some aspects of debugging, and we’ll use it to view our data when we pull it. Basically, RStudio persists data structures, plots, and a running history of your console output into a collection called a “Project.” This makes organizing working projects and switching between them very simple (once you’ve gotten comfortable with the construct). It also supports code editing, in that you can work on a dataset in memory without continually rerunning the code to pull that data in.

- Pane 4: Files/Plots/Packages/Help — this is where we’re actually going to plot our data. But, it’s also where help content shows up, and it’s where you can manually load/unload various “packages” (which we’ll also get to in a bit).

There is a more in-depth description of the RStudio panes here, which is worth taking a look into once you start digging into the platform more. For now, let’s stay focused.

Key Concept #1: R is interesting in that there is a seamless interplay between “the command prompt” (Pane 2) and “executable script files” (Pane 1). In some sense, this is analogous to entering jQuery commands on the fly in the developer console versus having an included .js file (or JavaScript written directly in the source code). If you don’t mess with jQuery and JavaScript much, though, that’s a worthless analogy. To put it in Excel terms, it’s sort of like the distinction between “entering a formula in a cell” and “running a macro that enters a formula in a cell.” Those are two quite different things in Excel, although you can record a macro of you entering a formula in a cell, and you can then run that macro whenever you want to have that formula entered. R has a more fluid — but similar — relationship between working in the command prompt and working in a script file. For instance:

- If you enter three consecutive commands in the console, and that does what you want, you can simply copy and paste those three lines from the console into a file, and you’re set to re-run them whenever you want.

- Semi-conversely, when working with a file (Pane 1), it’s not an “all or nothing” execution. You can simply highlight the portion of the code you want to run, and that is all that runs. So, in essence, you’re entering a sequence of commands in the console.

Still confusing? File it away for now. The seed has been planted.

Key Concept #2: Packages. Packages are where R goes from “a generic, data-oriented, platform” to “a platform where I can quickly pull Google Analytics data.” Packages are the add-ons to R that various members of the R community have developed and maintained to do specific things. The main package we’re going to use is called googleAnalyticsR (as in “R for Google Analytics”). (There’s a package for Adobe Analytics, too: RSiteCatalyst.)

The nice thing about packages is that they tend to be available through the CRAN repository…which means you don’t have to go and find them and download and install them. You can simply download/load them with simple commands in your R script! It will even install any packages that are required by the package you’re asking for if you don’t have those dependencies already (many packages actually rely on other packages as building blocks, which makes sense — that capability enables the developer of a new package to stand on the shoulders of those who have come before, which winds up making for some extremely powerful packages). VERY handy.

One other note about packages. We’re going to use the standard visualization functions built into R’s core in this post. You’ll quickly find that most people use the ‘ggplot2’ package once they get into heavy visualization. Tom Miller actually wrote a follow-on post to this blog post where he does some additional visualizations of the data set with ggplot2. I’m nowhere near cracking that nut, so we’re going to stick with the basics here.

Step 5: Finally! Let’s Do Some R!

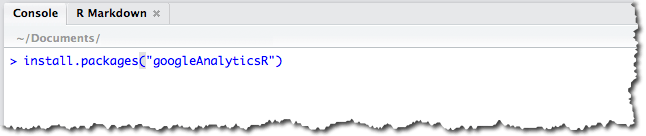

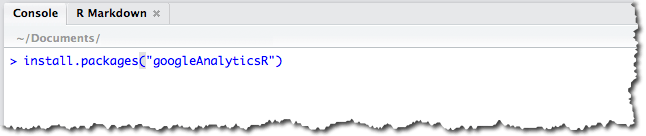

First, we need to install the googleAnalyticsR package. We do this in the console (Pane 2):

- In the console, type:

install.packages("googleAnalyticsR")

- Press Enter. You should see a message that is telling you that the package is being downloaded and installed:

That’s largely a one-time operation. That package will stay installed. You can also install packages from within a script… but there’s no need to keep re-installing it. So, at most, down the road, you may want to have a separate script that just installs the various packages you use that you can run if/when you ever have a need to re-install.

We’re getting close!

The last thing we need to do is actually get a script and run it. If analyticsdemystified.com wasn’t embarrassingly/frustratingly restricted when it comes to including code snippets, I could drop the script code into a nice little window that you could just copy and paste from. Don’t judge (I’ve taken care of that for you). Still, it’s just a few simple steps:

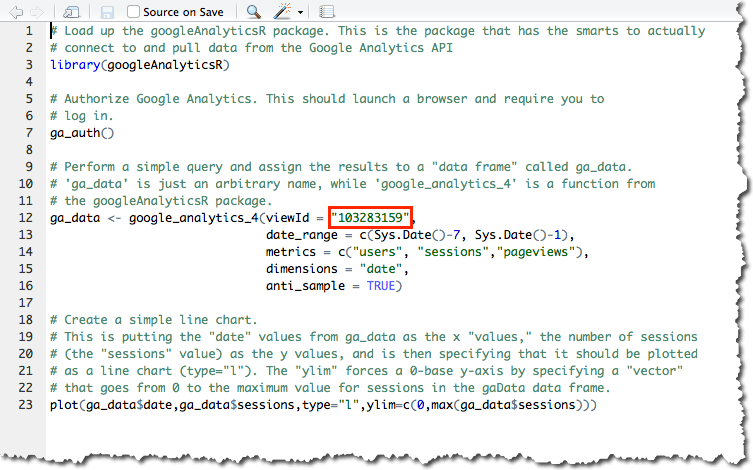

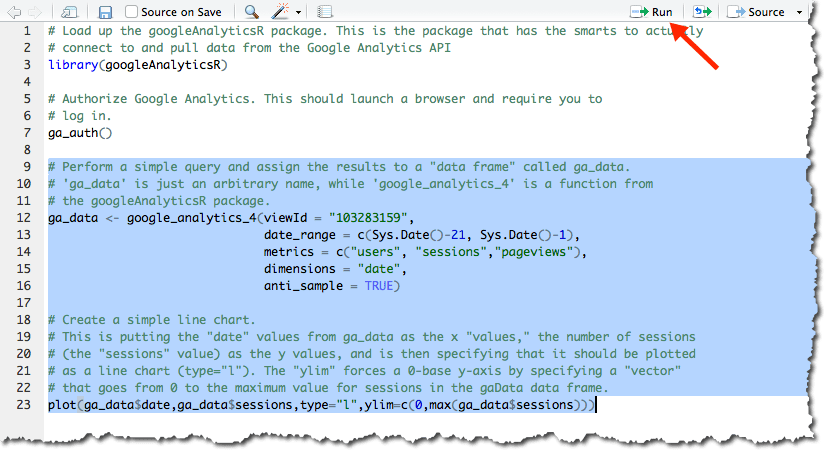

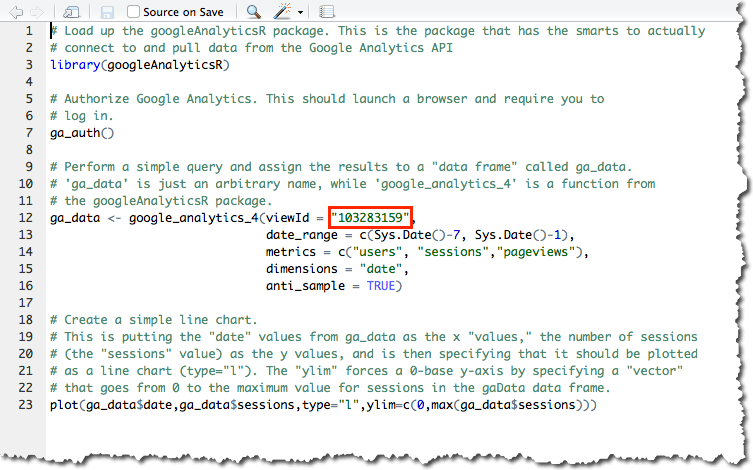

- Go to this page on Github, highlight the 23 lines of code and then copy it with <Ctrl>-C or <Cmd>-C.

- Inside RStudio, select File >> New File >> R Script, and then paste the code you just copied into the script pane (Pane 1 from the diagram above). You should see something that looks like the screen below (except for the red box — that will say “[view ID]”).

- Replace the and

[view ID] with the view ID you’d found earlier..

- Throw some salt over your left shoulder.

- Cross your fingers.

- Say a brief prayer to any Higher Power with which you have a relationship.

- Click on the word Source at the top right of the Pane 1 (or press <Ctrl>-<Shift>-<Enter>) to execute the code.

- With luck, you’ll be popped over to your web browser and requested to allow access to your Google Analytics data. Allow it! This is just allowing access to the script you’re running locally on your computer — nothing else!

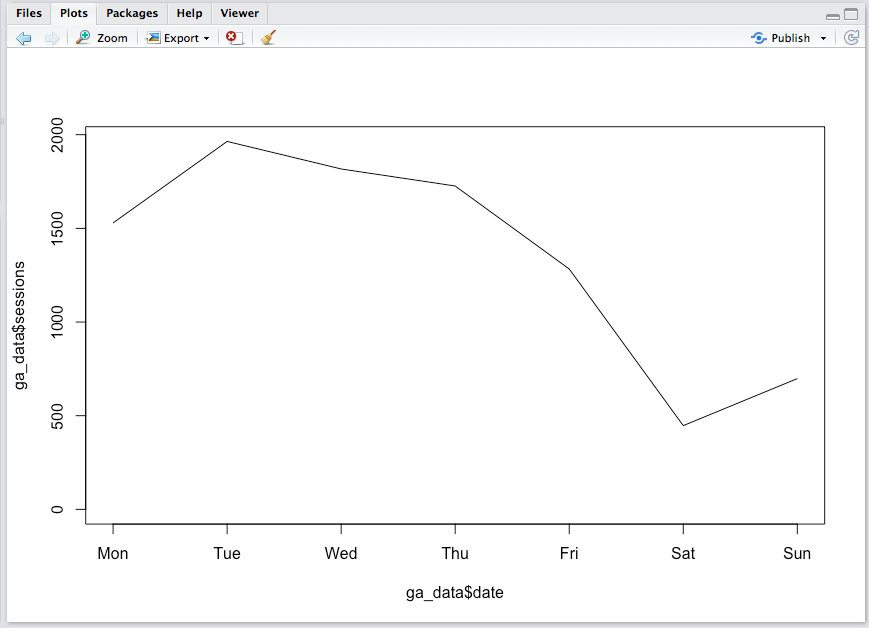

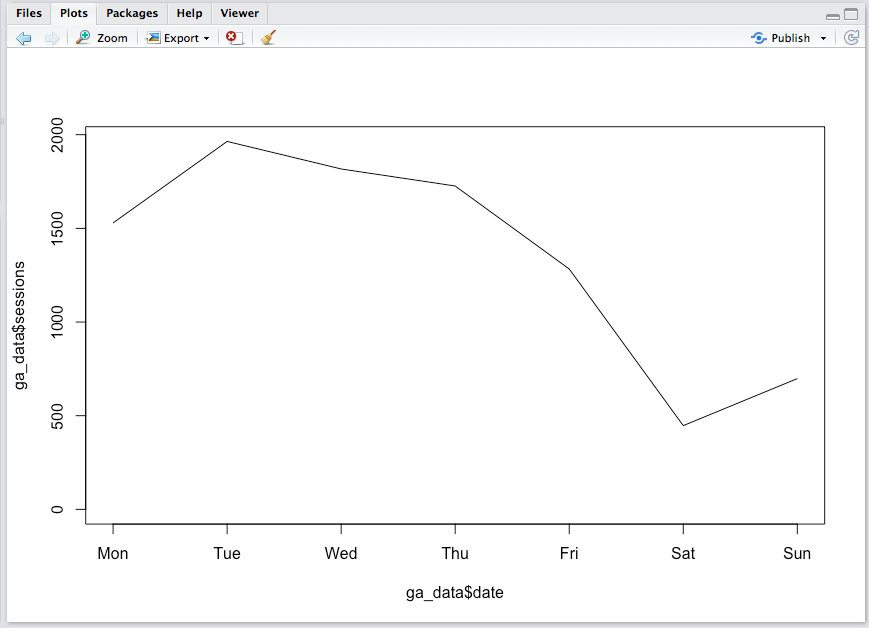

If everything went smoothly, then, in pane 4 (bottom right), you should see something that looks like this (actual data will vary!):

If you got an error…then you need to troubleshoot. Leave a comment and we’ll build up a little string of what sorts of errors can happen and how to address them.

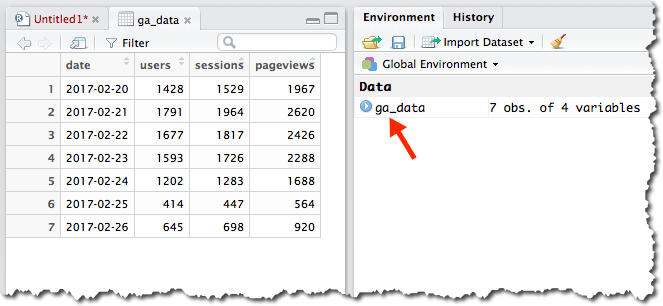

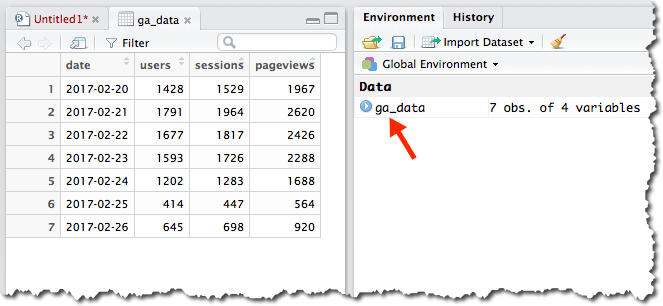

One other thing to take a look at is the data itself. Keep in mind that you ran the script, so the data got created and is actually sitting in memory. It’s actually sitting in a “data frame” called ga_data. So, let’s hop over to Pane 3 and click on ga_data in the Environment tab. Voila! A data table of our query shows up in Pane 1 in a new tab!

A brief word on data frames: The data frame is one of the most important data structure within R. Think of data frames as being database tables. A lot of the work in R is manipulating data within data frames, and some of the most popular R packages were made to help R users manage data in data frames. The good news is that R has a lot of baked-in “syntactic sugar” made to make this data manipulation easier once you’re comfortable with it. Remember, R was written by data geeks, for data geeks!

How Does It Work?

I’m actually not going to dig into the details here as to how the code actually works. I commented the script file pretty extensively (a “#” at the beginning of a line is a comment — those lines aren’t for the code to execute). I’ve tried to make it as simple as possible, which then sets you up to start fiddling around with little settings here and there to get comfortable with the basics. To fiddle around with the get_ga() settings, you’ll likely want to refer to the multitude of Google Analytics dimensions and metrics that are available through the core reporting API.

A Few Notes on Said Fiddling…

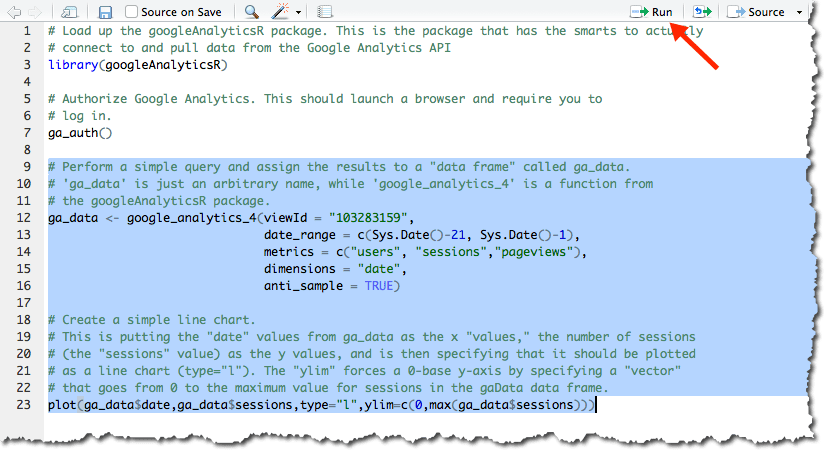

Running a script isn’t an all-or nothing thing. You can run specific portions of the script simply by highlighting the portion you want to run. In the example below, I changed the data call to pull the last 21 days rather than the last 7 days (can you find where I did that?) and then wanted to just run the code to query the data. I knew I didn’t need to re-load the library or re-authorize (this is a silly example, but you get the idea):

Then, you can click the Run button at the top of the script to re-run it (or press <Ctrl>-<Enter>).

There’s one other thing you should definitely try, and that has to do with Key Concept #1 under Step 4 earlier in this post. So far, we’ve just “run a script from a file.” But, you can also go back and forth with doing things in the console (Pane 2). That’s actually what we did to install the R package. But, let’s plot pageviews rather than sessions using the console:

- Highlight and copy the last line (row 23) in the script.

- Paste it next to the “>” in the console.

- Change the two occurrences of “sessions” to be “pageviews”.

- Press <Enter>.

The plot in Pane 4 should now show pageviews instead of sessions.

In the console, you can actually read up on the plot() function by typing ?plot. The Help tab in Pane 4 will open up with the function’s help file. You can also get to the same help information by pressing F1 in either the source (Pane 1) or console (Pane 2) panes. This will pull up help for whatever function your cursor is currently on. If not from the embedded help, then from Googling, you can experiment with the plot — adding a title, changing the labels, changing the color of the line, adding markers for each data point. All of this can be done in the console. When you’ve got a plot you like, you can copy and paste it back into the script file in Pane 1 and save the file!

Final Thoughts, and Where to Go from Here

My goal here was to give analysts who want to get a small taste of R that very taste. Hopefully, this has taken you less than an hour or two to get through, and you’re looking at a (fairly ugly) plot of your data. Maybe you’ve even changed it to plot the last 30 days. Or you’ve specified a start and end date. Or changed the metrics. Or changed the visualization. This exercise just barely scratched the surface of R. I’m not going to pretend that I’m qualified to recommend a bunch of resources, but I’ve include Tom’s and Jason’s recommendations below, as well as culled through the r-and-statistics channel on the #measure Slack (Did I mention that you can join that here?! It’s another place you can find Jason and Tom…and many other people who will be happy to help you along! Mark Edmondson — the author of the googleAnalyticsR package — is there quite a bit, too!). I took an R course on Coursera a year-and-a-half ago and, in hindsight, don’t think that was the best place to start. So, here are some crowdsourced recommendations:

And, please…PLEASE… take a minute or two to leave a comment here. If you got tripped up, and you got yourself untripped (or didn’t), a comment will help others. I’ll be keeping an eye on the comments and will update the post as warranted, as well as will chime in — or get someone more knowledgeable than I am to chime in — to help you out.

Photo credit: Flickr / jonny2love

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel:

To illustrate, let’s think about how we view traffic by channel: Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in

Several statistically-savvy analysts I have chatted with have said something along the lines of, “You know, really, to ‘get’ statistics, you have to start with probability theory.” One published illustration of this stance can be found in

I’d love to say that the development of this app (if you’re impatient to get to the goodies, you can check it out

I’d love to say that the development of this app (if you’re impatient to get to the goodies, you can check it out

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to

(This post has a lengthy preamble. If you want to dive right in, skip down to